IJDTSA Vol.1, Issue 2 No.5 pp.49 to 62, December 2013

Adaptation with Social vulnerabilities and Flood Disasters in Sundarban Region: A Study of Lodha Tribes in Sundarban, West Bengal

Abstract

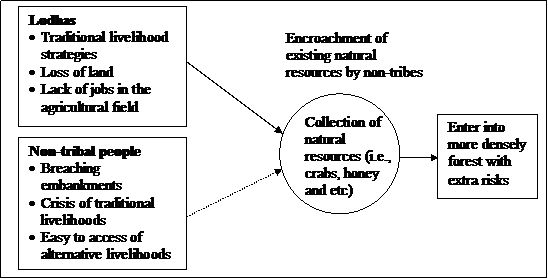

The Lodha tribes in Sundarban are mainly dependent on natural resources in Sundarban which have been encroached by non-tribal communities due to the livelihood crisis after inundation. The ethnographic research in two hamlets of Pathar pratima block in South 24 Pargana explores the existing socio-cultural deprivation of the Lodha tribes in the Sundarban region and how they become vulnerable to saline water floods and the livelihood strategies to deal with flood disasters. It is found that Lodha people live at very close river embankment which is the most vulnerable to destroy during high tides. As they do not depend on agricultural activities, the floods do not have any direct impact on them. But the impacts are experienced due to encroachment of their existing sources of livelihoods by the non-tribal communities after flood. As a result Lodha people started enter into more densely forest to search for livelihood with taking more risk.

Introduction

Disaster is a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or society causing widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses which go beyond the day-to-day ability of the affected community or society to cope with using its own resources (ISDR, 2002). EM-DAT (2007) shows that in the world total 33,733 people died in 2006 due to disasters while 20,572 people of these were from Asia. Among the disasters, floods are of foremost importance in terms of loss of human lives and properties. Asian countries are most vulnerable to flood disasters which have been aggravated due to environmental degradation. Between 1997-2006 Asian countries faced total 547 flood disaster which costed 115,506 million dollar (EM-DAT, 2007). In India about 80% geographical area is susceptible to natural and man-made disaster. On an average, disasters losses amount to 2% of India’s GDP and about 12% central government revenues (Ray-Bennett, 2007:420). Since 1953, disasters have affected in total 40,967 million people and damaged 3.725 million hectors crops which have costed around Rs. 1095.132 crore and total national disaster loss is around Rs. 2706.243 crore. In India, about 40 million hectors land is highly prone to floods which spread across the Indo-Gangetic plains and 5700 km coastline. The total amount of losses and destruction due to flood disaster covers 60% of total disaster losses in India (NIDM, 2009; GoI, 2002:190-192). West Bengal is one of the most flood prone states in India. Presently, 42.3% geographical area of the state is susceptible to floods which cover 110 blocks in 19 districts. Historically, the serious flood disaster occurred in 1787, 1806, 1823, 1831, 1834, 1838, 1848, 1856, 1866, 1876, 1885, and in 1890. Mainly southern part of the West Bengal is most prone to floods due to its geographical location. Recently, the experts working on climate change have also suspected more destruction and losses due to increasing sea level. As a result the flood disasters situation in coastal region of West Bengal has been aggravated. The socio-economically deprived tribal people living at the coastal area can not find the difference of disaster from their daily difficulties. The paper explores the existing difficulties and discrimination of the tribal people and post disaster difficulties in coastal area.

Disasters in Sundarban

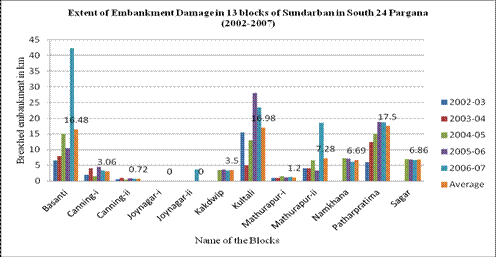

Bay of Bengal is known for cyclones during the pre and post monsoon season. The geographical location of Sundarban becomes vulnerable to cyclones. According to Hazra et al (2002), the frequency of cyclone has not changed, but increasing magnitudes of cyclone destroys huge public and private resources. Synchronization of timing of flood waters in the river with high tide in estuaries often lead to breaks in the embankments. This situation is further aggravated during the cyclone. The serious flood disaster occurred in 1982 and 2009 when most of Sundarban Deltas were affected by breaching embankment and flood. The flooding by saline water added extra burden and making more vulnerable groups who are living in below poverty line and dependent on agriculture. As most of the people are dependent on agriculture, whole economic activities depend on embankments.

Hazra et al (2002) have claimed that, sea level is rising @3.14 mm per year and increasing sedimentation load on sea-river bed is 0.1mm per year. So, the annual rising of sea level is 3.24mm per year which often causes saline water flood risk during the monsoon season as well as during the cyclone with synchronization of high tides. The researchers have established correlation between the increasing sea level and land erosion which mainly observed in the south and south-eastern part of Sundarban because total 251.961 sq km lands have been encroached by the river and sea by 1969-2009 which created large number of landless households and refugee. The most affected blocks are Sagar, Namkhana, and Pathar Pratima, Kakdwip of Kakdwip Subdivision.

Though breaching embankment is very common in Sundarban region, people are not similarly affected at the same island. The hamlets close to the river embankment or sea shore are most vulnerable to breaching embankment and the household those who have agricultural land close to river embankment are more affected than others. Destruction of embankment causes saline water inundation and physical loss of land due to encroachment. Though saline water inundation and river encroachment created problem in flood affected hamlet or village, all families are not affected equally because of their dependency on loss of resources and livelihood.

Tribes in Sundarban

‘Sundarban’ literally means beautiful forest which is the name by dominant tree ‘Sundari’ (Heretiara Litoralis). Apart from providing home to an important number of rare and endangered flora and fauna, it is the only mangrove forest in the world inhabited by tigers. The history of the human settlement had been started during Khan Jahn’s period when he passed a ‘Jagir’ in 1459 in Sundarbans. The actual land reclaimation had been stared during 1765 and 1770 by patronize of Collector General Claud Russell. The Colonial government wanted to convert the mangrove forest into safe and productive agricultural field and therefore government distributed the land to Bengali local lands lords for long term lease. Socially and economically marginalized people from Midnapur district, Bankura, Purulia, Howra and neighbourning states came as labourer to clean the forest, construct the embankment and converted the land into productive agricultural land. Many labourers left the Sundarben after cultivation but many of them are staying permanently. Now the total population is 42,00,000 which spreads over eighteen blocks (GoI-2001).

The migrants belong to scheduled castes (Chandal, Namasudra, Pods, Bagdi) and scheduled tribes people and lower status upper caste Hindus, Muslim and others. Among the tribal people Santal, Munda, Oraon, Bhumij, Kora, Chero, Ho, Baiga, Lodha and Khond are the majority. At the beginning, tribal people were brought into Sundarban to work as labourer. After acquiring the agricultural land, they involved into cultivation but a large numbers of households are still landless labourer as well as marginal landowners. Due to extensive educational system, many well educated new generation tribal people engage with government and non government jobs also, but they are very few. According to Census report (GoI, 1991), 35.80 % tribal people in Sundarban were main worker, 59.17% were non-worker and 5.03% were marginal worker. Though the tribal people who first entered into this virgin land, they are socially, economically and politically marginalized in compare to dominant Hindus and Muslims Bengalis. Among the tribal people the Lodhas tribes are very less in numbers who spreads in different hamlets in Sundarban.

Literature Review

Though there are debates in conceptualizing the ‘disaster’, social scientists have rejected the religious approach as well as environmental approach and defined ‘disaster’ is an interface between extreme physical environment and vulnerability. The vulnerability to disasters can not be determined only by the wealth. It is determined by a complex range physical, economic, political, and social factors (Manyena, S.B. 2006:440; Turvey, R. 2007: 243; Sarewitz, D et al. 2003: 809,810; Hogan, D.J and Marandola, E, Jr. 2005: 456; Cutter, S. L et al. 2003: 242).The idea of vulnerability is very important because it permits the researcher to study the dynamics of disaster which are beyond the natural phenomena. The conceptual framework of vulnerability was borne out from the difficulties of everyday life (Furedi, F, 2007:488).

The political economists working on disaster management have given more importance to understand the causes of disaster risk. They argue that, disaster can not be understood without knowing the disaster vulnerability. The Pressure and Release model of Wisner is widely used to understand different dynamics of vulnerability. According to the model, ‘Pressures’ are generated by the vulnerability and the impacts of hazards. The ‘Release’ idea is incorporated to conceptualize the reduction of vulnerability and hazard impacts. The ‘vulnerability’ in Pressure model of PAR has been explained in three levels i.e., root causes, dynamic pressure and unsafe condition (Wisner et al., 1994:23).

The root causes (underlying causes) of vulnerability are economic, demographic, and political processes. The root causes are the function of economic structure, political structure, and legal definition of rights of ideological order. The ‘Root causes’ are connected with the functioning of the state and ultimately police and military. The political and economic structure of a society also controls the distribution power. As a result, marginalized people are having less access of political power. So, the access of less political power creates two types of vulnerabilities; firstly their access to livelihoods and resources and secondly, they are likely to be low priority for government interventions intended to deal with hazard mitigation (Wisner et al., 1994:24).

The dynamic pressures are the processes and activities which translate the root causes into vulnerability of unsafe conditions. It includes rapid population growth, epidemic disease, rapid urbanization, war, foreign debt and structural adjustment, export promotion, mining, hydropower development, deforestation work through to localities and decline in soil productivity (Wisner, 1994:24). As a result local people are unable to cope with the adverse situation.

Unsafe conditions are the specific forms in which the vulnerabilities are expressed in time and space in the conjunction of hazard. Unsafe conditions include living at dangerous geographical locations, inability to afford safe buildings, lack of effective protection by the state (for instance, in terms of effective building codes), dependency on dangerous livelihoods (such as ocean fishing in small boats, or wildlife poaching, or prostitution, with its health risks), and minimal food entitlements (Wisner et al., 1994:25).

Wisner et al., (1994) argue that numbers ‘hazards’ are not increasing and it is the existing and increased vulnerabilities which have been transformed into disaster risk by the interaction with hazards. Though the poor tends to be most vulnerable to disaster risk, vulnerability is not because of poverty. Vulnerability is the characteristics of a person or a group in term of their capacity to anticipate, to resist and to recover from the impact of disasters (Wisner et al., 1994). It can be understood by the economic status, social discrimination, and individual vulnerability. ‘Being vulnerable’ is ‘being prone to suffer’. The daily-life of large number of socially deprived people is not different from living conditions of those hit by disaster because they hardly find little freedom to choice where and how to live.

It is also found that, most of the vulnerable people do not receive early warning before the extreme event. As a result disaster destruction and losses due are higher among the vulnerable people. Researchers also argue that, evacuation orders do not function among vulnerable communities, because, vulnerable people are highly attach to their material and economic resources. The study on floods in Texas, USA has shown that, the physical losses and destruction are quite higher among the Afro-Americans than American. It is because of geographical location, low access of political power, and less economic strength. Bolin (2007) has seen the social discrimination of black people during the Hurricane Katrina as a product of contemporary social, political and economic marginalization. The disaster vulnerability of Afro-American people is the long history of ethnic deprivation by the politically, socially and economically dominant white people.

In India, social deprivation is also an important factor of disaster which is also found in USA during the Katrina disaster. In this context, Gandhi’s comment is very insightful for understanding the reality of Bihar earth quake in 1934. He said “I want you everyone to be superstitious enough with me to believe that this disaster is a divine chastisement for the great sin we have committed, and are still committing, against those whom we call untouchables ……..” (cf Roy, 2008:283).

According to Samanta (1997), impacts of disaster depend on capacity and adaptability with the extreme event. The study on coastal region of West Bengal has shown that, farmers totally dependent on agricultural land suffer a lot due to saline water inundation but the Bangladeshi farmer desires floods in every three-four years. According to the researchers, the flood water carry huge amount of silt which develops fertility of the soil. Therefore the disaster impact on the affected people can be understood from the context of crisis of livelihood and coping strategies to recover from the existing and added crisis within the community.

Research Objectives

Though socio-economically marginalized people migrated into Sundarban islands, the tribal people are socio-economic and culturally deprived in compare to dominant Bengalis. Therefore the main objectives of this paper are:

Research methodology and data collection

Bose et al. (2008) said that, 45.2% Lodha males have high rates of CED (Chronic Energy Deficiency) i.e., BMI≤18.5 kg/m 2 and they are in serious nutritional stress. Though there are differences into their food habits, inadequate dietary intake due to poor socio-economic status is the main factor of their low BMI. The Lodha hamlets have been selected for conducting the research because they have been living with existing chronic vulnerabilities. Though they are different from Santal, Munda and Oraon, they are identified as Sardar for non tribal communities. To explore the disaster vulnerabilities, Lodha hamlets of Ram Ganga Gram Panchayat and G-Plot Gram Panchayat in Pathar Pratima Block have been selected for conducting the study. To explore the existing social vulnerability and post disaster vulnerability, research followed ethnographic approach for two purposes: a) to elaborate cultural diversities through a close study of a small group of Lodha tribe and b) to explore culture specific disaster vulnerability of a small community. The secondary data has also been collected from published articles, hand books and unpublished state government reports.

Lodhas in Sundarban

Lodhas were known as criminal tribe until 1952 and when they became ex-criminal tribes by the repeal of Criminal Tribes Act of Government of India. In West Bengal they are recognized as denotified scheduled tribe after August 1955. The word ‘Lodha’ may be a corrupt form of word ‘Lubdhaka’ meaning a trapper. But Lodha prefer to be called as ‘Savaras’ or ‘Lodha-Savaras’, because they raced their origin from the Savaras who were attendants to Rama of the Ramayana. They akin to the Khariays of the neighbouring districts and pride themselves as superior to other allied tribes. Lodhas are the inhabitant of West Midnapur and mainly in Jhargram sub-division. They moved towards other neighboring districts Purulia, Hoogly, Birbhum, and border districts of Jharkhand and Orissa due to deforestation and crisis of livelihoods. Originally they migrated from the place Lodh or Nodh or Ludhi of Central Province. Risley (1891) identifies them as sub-tribes of sub-tribe of the Bhumij in Chotonagpur. They use ‘Savar’ as their surname in jungle area but they use Bhakta, digar, malik, Bag, Nayek, Ahori, Bhuina, Pramanik, Dandapat and Kotal as their surname in deforested area (Singh, 1994).

Lodhas can be grouped into two major groups: a) Lodhas of forest area; and b) Lodhas of deforested areas. The lodhas of deforested area have taken agriculture and agricultural labour work as main source of livelihood. Apart from the agriculture and agricultural related livelihood, they also collect wood from the forest, hunting and trapping the animals. They moved into neighbouring districts and border districts of Jharkhand and Orissa. During the day, they travel in the guise of snake charmers and offer for sell various articles to the people of the locality and engage in criminal activities at night. The women and children also involved into criminal activities with male members by selling stolen ornaments and goods. The Lodhas were not originally criminal in nature. When they were driven out from their primitive dwelling in forests, they took to criminal activities to make a living. The community is ruled by the Mukhiya or village headman who holds the highest position and is obeyed by others. They maintain friendly relations with members of others communities viz., Santals, Mumdas, Koras, Mahalis and Mahatos’

A small number of lodhas came to Sundarban, but most of them went back to Midnapur. A small number of Lodhas spreads in all over the island. Though there are three Lodha hamlets in Pathar Pratima Block, the hamlets in Satyadaspur village of G-Plot Gram Panchayat, Shibpur village have been selected for conducting the research.

Table1: Tribal situation in 24 Pargana 1872-1921 (adopted from Mukhopadhyay, 1976)

|

Name of Tribes |

Year |

||||

|

1872 |

1891 |

1901 |

1911 |

1921 |

|

|

Bhumij |

660 |

5,306 |

9568 |

12225 |

11015 |

|

Garo |

2 |

– |

– |

|

– |

|

Kharria |

7 |

– |

– |

22 |

– |

|

Kol |

389 |

6253 |

– |

|

– |

|

Santhal |

814 |

1499 |

2233 |

– |

– |

|

Oraon |

3362 |

663 |

5931 |

5538 |

2045 |

|

Lodha-Savar |

18 |

– |

35 |

– |

|

|

Munda |

– |

688 |

9229 |

5896 |

5564 |

|

Kora |

– |

144 |

– |

463 |

– |

|

Mahilis |

– |

73 |

– |

154 |

– |

|

Malpaharias |

– |

– |

– |

8 |

– |

Research Site

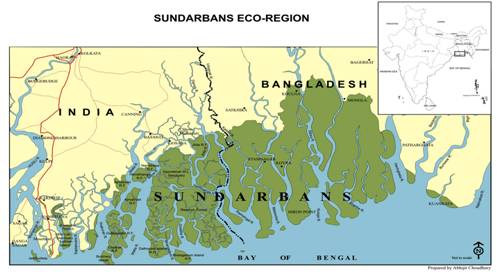

Sundarbans spread over the area of 9630 square kilometer in the district of North 24 Parganas and South 24 Parganas of West Bengal, India. Sundarbans region is located between 21 0 31 ’ – 22 0 38 ’ N Lat and 88 0 5’ -90 0 28’ E Long, covering a forest area of 4284 square kilometer which comprises 102 deltas. Presently 54 deltas are inhabited by people, which cover 4284 square kilometers (Bera et al, 2006:7). Sundarban deltas were formed by the deposited sediments from three major rivers i.e., the Ganga, Brahmputra, and Meghna and their dense network of smaller rivers, channels. The maximum elevation is only 10 meter above the mean sea level. The western limited of Indian Sundarban is demarcated by Hoogly River and eastern boundary is Raimangal River. Pather Pratima Block is a Part of Sundarban region which is situated in south-eastern part of Kakdwip Sub-Division. It covers 484.47 sq. km where only 4784.20 hectare land is covered under forest. The average depth of availability of ground water level is 16 feet.

Table3: Gram Panchyat wise geographical area of Pathar Pratima Block (in hectare)

|

Name of Gram Panchyat |

Cultivable land (in hectare) |

Forest (in hectare)

|

|

Dakshin Gangadhar Pur |

2585 |

– |

|

Dakshin Rai Pur |

1451 |

– |

|

Digampur |

2536 |

– |

|

Sri Narayan Purnachandra Pur |

1757 |

– |

|

Ramganga |

1962 |

– |

|

Durbhachati |

1795 |

– |

|

Gopalnagar |

1912 |

– |

|

Achintyanagar |

3496 |

– |

|

Patharpratima |

3257 |

– |

|

Banashyamnagar |

2299 |

– |

|

Sridhannagar |

2026 |

4340.66 |

|

BrajaballavPur |

2481 |

– |

|

G-Plot |

4184 |

443.54 |

|

Herombogopal Pur |

2100 |

– |

|

Lakshijanardan pur |

2232 |

– |

|

Total |

33,488 |

4784.20 |

Initially Sundarban was no mans’ land. Mainly tribal and lower caste people from different part of West Bengal and India were brought for clearing the forest. These inhabitants of Sundarban got their livelihood from forest, rivers and reclaimed land. It is found that lower caste Hindus and Muslims reside in north and eastern part of this region. Among the low caste Hindus, ‘Pods’ were numerous in north and north-west, ‘Namasudra’ and ‘Chandal’ concentrated in east, and ‘Mahishya’ resided in south and south-west and as well as South-eastern part of Sundraban. Mahishya is the major upper caste Hindu in this region. Among the Muslim Fargis are dominant (Chottopadhya, 1995; Basu 2006). The total population was tremendously increased during 1951 and 1971. The main reason was massive migration during 1947 and Bangladesh ‘Mukti Judho (1971).

Table6: Increasing population of Sundarbans since 1872-2001 (GoI, 2001)

|

Year |

Population |

|

1872 |

2,96,045 |

|

1881 |

3,55,512 |

|

1891 |

4,19,818 |

|

1901 |

4,87,377 |

|

1911 |

5,70,878 |

|

1921 |

6,48,654 |

|

1931 |

7,54,421 |

|

1951 |

11,59,559 |

|

1961 |

15,32,101 |

|

1971 |

20,03,097 |

|

1981 |

24,55,365 |

|

1991 |

32,05,528 |

|

2001 |

42,00,000 |

Pathar Pratima Block is situated in south-eastern part of Sundarban region where as most of the people were emigrated from Midnapore District. Most of the people are ‘Mahishya’ followed by other backward caste and Bagdi community. The tribal people are 2834 (Pathar Pratima Block report, 2008).

Table8: Population distribution of all Gram-Panchyats of Pathar Pratima Block, 2008

|

Gram Panchyats |

Scheduled caste |

Scheduled tribe |

OBC |

General |

||||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

|

Dakshin Gangadhar Pur |

3509 |

2937 |

128 |

108 |

4710 |

4029 |

3699 |

3522 |

|

Dakshin Rai Pur |

2408 |

1594 |

84 |

55 |

2575 |

2475 |

2412 |

2216 |

|

Digampur |

3802 |

2747 |

127 |

110 |

4565 |

4238 |

3905 |

3829 |

|

Sri Narayan Purnachandra Pur |

2700 |

1452 |

85 |

61 |

2803 |

2481 |

2700 |

2686 |

|

Ramganga |

2498 |

2004 |

95 |

85 |

3543 |

3511 |

3200 |

3072 |

|

Durbhachati |

2781 |

1732 |

90 |

75 |

3300 |

2804 |

2975 |

2902 |

|

Gopalnagar |

2300 |

1595 |

75 |

67 |

2868 |

2570 |

2801 |

2726 |

|

Achintyanagar |

3245 |

2515 |

120 |

104 |

4301 |

4178 |

4045 |

3994 |

|

Patharpratima |

3755 |

2994 |

145 |

121 |

5208 |

4871 |

4800 |

470 |

|

Banashyamnagar |

2255 |

1975 |

90 |

74 |

3095 |

3029 |

3002 |

2882 |

|

Sridhannagar |

2702 |

1447 |

85 |

74 |

3110 |

2798 |

2922 |

2780 |

|

BrajaballavPur |

2842 |

2491 |

104 |

100 |

3901 |

3781 |

3605 |

3576 |

|

G-Plot |

3609 |

2790 |

138 |

119 |

4865 |

4486 |

4805 |

4783 |

|

Herombogopal Pur |

2699 |

2181 |

101 |

93 |

3850 |

3500 |

3609 |

3485 |

|

Lakshijanardan pur |

2492 |

1880 |

90 |

83 |

3180 |

3023 |

3301 |

3220 |

|

Total |

43,597 |

32,334 |

1,557 |

1,329 |

55,874 |

51,774 |

51,781 |

46,143 |

Table9: Literacy rate of Pathar Prtima Block, 2008

|

Scheduled caste |

Scheduled tribe |

OBC |

General |

||||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

41% |

32% |

28% |

26% |

67% |

58% |

89% |

74% |

Though initially large numbers of tribes came to Sundarban, most of them went back to before independence. The main reason was to adverse climate and deaths by the tigers. Though there were enough livelihood opportunities, they went back to Chotonagpur. Though they used to come seasonally till 1950s, the crisis of traditional livelihood started captured non-tribal people and they permanently went back. Among the tribal groups, Munda and Oraon are main but, there many small tribal communities in the sundarban. There are small numbers of Lodhas in Sundarban who came with other tribal and nontribal neighbours from Midnapur District of West Bengal and latter they also went back with other tribal neighbours. A small numbers Lodha people live at Shivpur village, Daspur village and West Dwarkapur village of Pathar Pratima block.

Social Life and Relationship of Lodha People with their Neighbours

The ‘Mahishya’, from Midnapur and Howra district, are the dominating Bengali community in Pathar pratima Block. They capture maximum agricultural land and economically dominant than Namasudra, Pod and Muslim. The abolition of jamindari system and land distribution process helps Lodhas to involve with active politics. As communist party was directly involve with land distribution process, they are influenced by the communism. Though they had got few pattas, the lands have been captured by non-tribal private money lenders. Therefore they become landless and completely depend on natural resources for their livelihood.

Rice is the main food grain for them which has been collected from PDS. Small fish, crab and egg are the source of protein which is collected from canal, river and forest. The Daal (pulses) are very rare menu into the meal. Preparing muri (pop rice) is very luxury for them and it is made during the Sitala puja only. They eat once a day either at morning or night and leave for whole day for catching and collecting fish, honey, crabs. Once they leave, they take kids with them and sometimes kids stay at home. Though the school is very close to them, they attend rarely. As the parents do not stay for whole day in the home, kids are not guided anybody but there are girls who go to the school. Once the girls take admission in high school, they are eligible to stay in school hostel. The school going children cannot adjust with their friends in the hamlet. The tribal head of their hamlets decides their social activities and cultural activities and the goddess Sitala temple is the main common place to discuss their social problem and disputes. Though they live with Munda, Orano, Hindu and Muslim people but they are isolated from the other tribes and Hindu and Muslim. Lodha hamlets are quite far from the Hindu and Muslim hamlets and they are contacted only for country liquor, political support and chanda for celebrating Hindu festival and monetary transaction. Lodhas are not invited by Hindu neighbours during their social festivals and public events. But non-tribal people are people are invited by Lodhas while they celebrate Sitala Pujo in the month of Chaitra.

Trading of natural resources becomes important for the tribes to interact with other villagers and traders because they are the main supplier for crabs and honey to the local traders. The contact and communication with the non-tribal families happens due to sell of crabs and Hental leaves in exchange of rice, vegetables, and fruits. Most of the cases buyer and sellers are women who do not carry enough cash. The influential non-tribal families close to the Lodha hamlets are the buyers of all the valuable materials which they collect from criminal activities. Sometimes they are forced to sell these materials in very low rate because of their poverty. Therefore it is only the profit making transaction, when non-tribal people communicate and contact with them.

The involvement into political party activities have given wider opportunity to the male tribal leader to met non-tribal people. They are the supporters of left political party and it becomes the target point for non left political leaders to attract them into their political party. The situation becomes very complicate during the Gram Panchayat election which causes disputes among the neighbours. Though the village headman decides the votes of entire hamlet, they do not have bargaining power as compare to non tribal people.

Economic activities

People were brought from the main land for different purpose. As the tribal people are habituated with forest environment, they were brought to cut the forest. The second group was Muslim and lower caste Hindu for constructing embankment or dykes. The last group was Mahishya Hindu who was the expert in cultivation. Though the segregation among the people on their basis work is difficult, the purpose of emigration was different. As the source of livelihood was little different from mainland to Sundarban, all people worked for reclaiming the forest, constructing the river embankment and cultivation on the basis of certain agreement with local landlord. Tribal people mainly came to this region as daily labourer to reclaim the forest. Traditionally Lodha tribes depend on catching crabs, collecting honey, begging and daily wage. Though Lodha people used to cultivate in a small plot of land, criminal activities in night was the main activities. But presently they mainly depend on natural resources and daily wage. They go out for collecting paddy from the rat holes during the harvest, catch small birds, tortoises, small fish from the river and public canal. Presently young generation Lodhas take lease a small plot of land from other tribe or non-tribal neighbous for cultivation during the Robi season. As they do not cultivate, the demand of vegetables is very high near to Lodha hamlet. Selling country liquor is very common the lodha families which becomes their another source of income. It is found that, though tribal people are not contacted by dominating Hindu and Muslim, they come for consuming liquor from their home.

Vulnerable location to stay

The location of Lodha hamlets are at the river side which is vulnerable to river encroachment due to breaching embankment and floods. There are many hamlets close to the river embankment was totally destroyed during the cyclone Aila, 2009 but, the destruction in tribal hamlets are not recovered after one year of the disaster. Though the river side location helps them to access boat and natural resources, it is the dominant Bengalis who do not absorb them into their hamlets. The destruction of embankment and river encroachment destroys their house, land and source of water and household materials. The destruction may happen at any time and any season during the full moon and first moon high tides.

‘The bund was poor. It was the Asanard month morning, and suddenly the embankment was breached and decoyed entire hamlets. I couldn’t collect any material. We were waiting at the safer part of the embankment till low tide started.…(59 year old respondent)’

Loss of livelihood and Disaster Vulnerability

The breaching embankment and saline water inundation directly do not create problem into their existing livelihood because there are few Lodha families who have small plot of agricultural land. They have different livelihood activities which based on natural resources as well as manual labour and criminal activities. But the criminal activities have been reduced due to police action. Though they seasonally go out and do daily wage labour work, catching crab and collecting honey and fish, tortoise becomes main source of income. They also collect small fishes from inland public pond or canals. As the government has put so much restriction, they can not cut the forest. As a result most of the Lodha families become dependent on catching crabs and seasonal hone collection. It is traders who give them lure or (adhar) to catch the crab and condition is that, they have sell their total catch to them. As the market price is good, they do not sell to families with the exchange of goods at their village.

Total 5-7 persons go for seven to ten days trip with uploading their boat with food and water and Adhar (lures) to catch crabs. They go to the dense forest for more availability of crabs; bigger size or weight of the crabs. They come back during the tides of full moon and first moon when forest becomes flooded during the high tide and the high tides during those days are very strong. But the total catches have reduced due to involvement of non-tribal communities into the catching. Due to continuously breaching embankment, saline water floods and river encroachment and good market price, a large numbers of non-tribal people also join into this livelihood activity. The situation becomes worse when disaster coverage a huge area and the numbers of crab catchers and honey collectors become increased. As the natural resource collection area is constant, the Lodha can not stop anybody to catch and as a result they move into more densely forest area to maintain their total catch to maintain their livelihood.

Fig2: Post disaster Livelihood crisis and strategies to adapt

On the other hand catching small fish and tortoises from the public canals and ponds is important income generating activities among the Lodhas during the off season of catching of crabs and collecting honey. The small fishes are the main source of protein for them and they sell tortoises to the villagers. But they do not get any fresh water fish species and tortoise after the saline water inundation. As a result, there is the reduction of total catches which create problem into their daily activities. But once they are entering into more densely forest, they are into the extra risk of their life.

Conclusion:

Though traditionally Lodhas are socially discriminated as criminal tribe by the non tribal People, they only communicated during the profit making transaction. The root causes of their livelihood crisis due to deforestation and encroachment of forest and forest resources are underestimated by the government. In Sundarban, the cultivated lands of these people have been captured by the non-tribal private money lenders which force them to live without property. Therefore saline water inundation does not have any direct impact on landless Lodhas. But loosing physical land has direct impact on them because they live at the river side. Though Lodhas get enough food grain from the PDS, purchasing capacity depends on their total catches and collection from the forest. But they losing the natural resources due to the involvement of non tribal communities into the catching and collecting resources forces to enter into densely forest. The deceasing livelihood opportunities force them to select more unsafe condition which may create actual disaster in their life.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)